The circumstances of a casualty’s death make for an interesting category of inscription; many manage to convey not only information but dignity and pathos too, despite their restricted letter count.

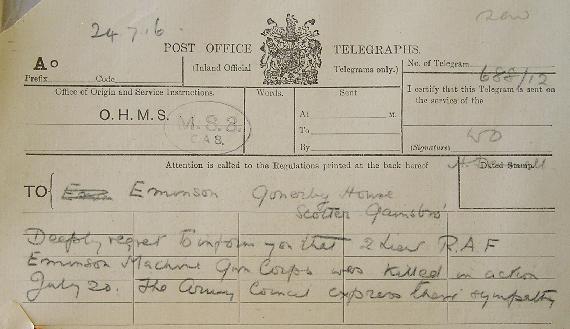

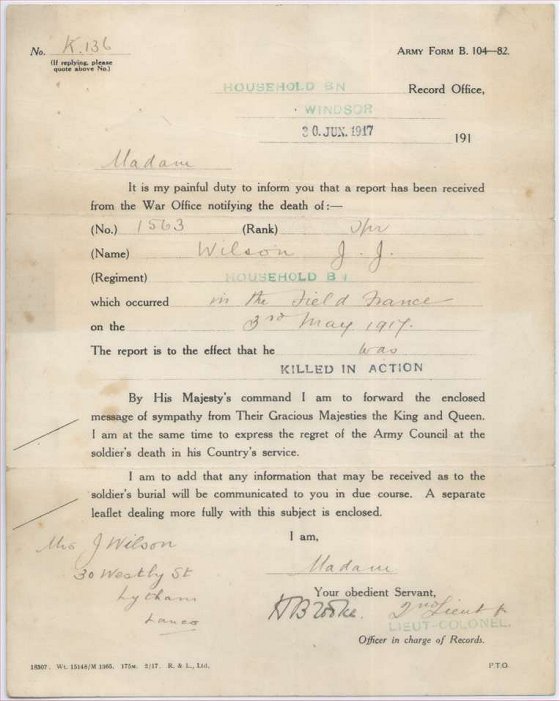

Some inscriptions quote “Killed in action” or “Died of wounds”, the words of the official communique. An officer’s next-of-kin received a telegram with the words: “Deeply regret to inform you that … was killed in action”, or had “died of wounds”. Soldiers’ received a letter: “It is my painful duty to inform you that a report this day has been received from the War Office notifying the death of …”, with “Killed in action” or “Died of wounds” stamped into the appropriate space. Despite the tragedy, there was a melancholy cachet to both the phrases. It meant that your relation had been a frontline solder, not a base wallah, which in turn meant that he had been passed Grade A at his medical, the top physical category. He was, however, still dead.

To have been killed in action a casualty must have died without receiving medical attention. Even if he only lived long enough to reach the Regimental Aid Post immediately behind the firing line he was still deemed to have died of wounds rather than to have been killed in action. Once some time had passed between a man being wounded and dying the next-of-kin were informed that he had ‘died, rather than ‘died of wounds’. I haven’t yet discovered whether there was a ruling about exactly how much time had to have passed before the distinction was made.

Take for example Lieutenant Dunn, his parents received a telegram telling them that their son had been “dangerously wounded” on 23 March 1916. When he died two days later the telegram informed them that he had “died of wounds”. However, John Byrne was told that his brother, Lance Sergeant Byrne, had ‘died’ in 9th General Hospital, Rouen. There’s no indication how long he’d been there. Lieutenant Dunn died at a Casualty Clearing Station, closer to the front line and therefore higher up the evacuation chain from a base hospital. The seriously wounded who had a chance of surviving were moved to base hospitals. Casualty Clearing Stations were for those who couldn’t be moved, or who were more lightly wounded and wouldn’t necessarily need to be in hospital for very long.

Of the two illustrated examples, Lieutenant Eminson’s parents were sent the telegram four days after he had been killed trying to bring in a wounded soldier through the barbed wire. His inscription makes no reference to this but rather quotes the Te Deum, ‘The noble army of martyrs praise thee’. Trooper Wilson was killed on 3 May. Initially his next-of-kin were only informed that he was missing and it wasn’t until 30 June that they were told that he was dead. There is no inscription on his grave.

This category of inscription provides a vivid insight into the conditions of battle, the random nature of warfare, individual tragedies and the instinctive selflessness of many men.

No Comments